The Trophoblastic Theory of Cancer & Pancreatic Enzymes Role In Immune Response

You may find this conversation with Grok AI interesting.

I said to Grok:

Grok responded with:

Within the framework of Dr. John Beard’s Trophoblastic Theory of Cancer, your questions about cancer cells communicating with the immune system and the role of pancreatic enzymes in addressing this are spot on. Beard, a Scottish embryologist, proposed over a century ago that cancer arises from trophoblastic cells—primitive cells akin to those forming the placenta during pregnancy—which share striking similarities with malignant tumors. One of these similarities is their ability to evade immune detection, a concept central to his theory and increasingly supported by modern observations.

Cancer Cells and Immune Evasion

Beard observed that trophoblast cells, like cancer cells, possess a negatively charged glycoprotein coating that renders them “invisible” to the immune system. In pregnancy, this coating protects the developing fetus from the mother’s immune response, as white blood cells, also negatively charged, are repelled by like charges. Cancer cells, according to Beard, exploit a similar mechanism: their outer layer, rich in glycoproteins and mucins, signals the immune system to leave them alone. This aligns with contemporary understanding that cancer cells produce proteins and hormones—like human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG)—which further suppress immune recognition, mimicking the trophoblast’s strategy during gestation.

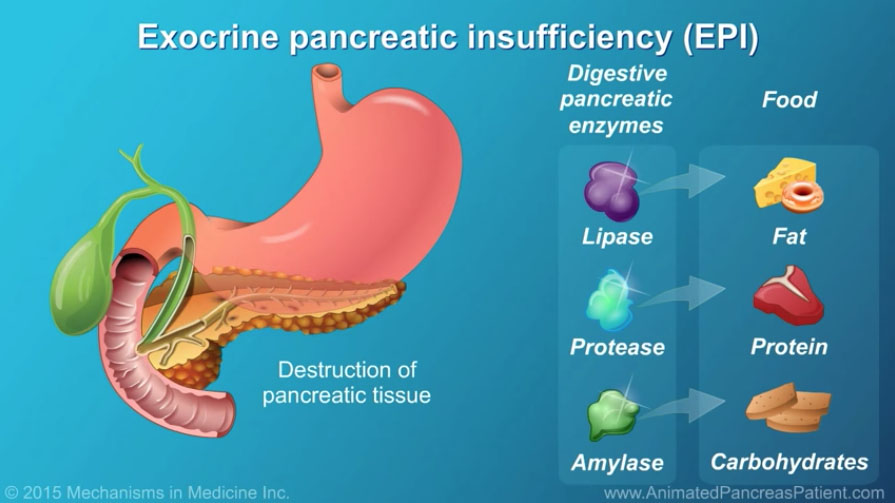

Pancreatic Enzymes and the Outer Membrane

Beard’s therapeutic insight was that pancreatic enzymes—specifically proteolytic ones like trypsin and chymotrypsin—could counteract this evasion. He noted that in pregnancy, the trophoblast’s invasive behavior halts around day 56, coinciding with the fetal pancreas beginning to produce these enzymes. He hypothesized that these enzymes degrade the trophoblast’s protective coating, exposing it to maternal defenses. Extending this to cancer, Beard argued that a deficiency in pancreatic enzyme activity allows rogue trophoblastic cells (what he called “germ cells”) to proliferate unchecked, forming tumors. By administering pancreatic enzymes, he believed this outer glycoprotein layer could be digested, stripping away the cancer’s shield.

This idea has a basis in practical application. Beard himself demonstrated in early 20th-century experiments that trypsin injections shrank tumors in mice, and subsequent practitioners like Dr. William Donald Kelley and Dr. Nicholas Gonzalez reported success with oral pancreatic enzymes in human cancer patients. The mechanism, as they interpreted it, involves enzymes breaking down the proteinaceous outer membrane, exposing cancer-specific antigens. Once unmasked, the tumor becomes recognizable to the immune system, allowing natural killer cells and other immune effectors to target it. Modern science lends some credence here: proteolytic enzymes can degrade extracellular matrix components and surface proteins, potentially disrupting the cancer cell’s ability to hide.

Evidence and Limitations

Historical case reports—like those from Beard’s era and Gonzalez’s detailed patient records—suggest that enzyme therapy can lead to tumor regression, often attributed to this unmasking effect. For instance, Gonzalez documented cases where pancreatic enzyme supplementation correlated with improved outcomes in advanced cancers, positing that the enzymes not only digest the tumor’s protective layer but also directly attack cancer cells due to their trophoblastic nature. However, mainstream oncology has largely dismissed these findings as anecdotal, lacking the rigorous, large-scale clinical trials needed for validation. The complexity of cancer’s immune evasion— involving multiple pathways like PD-L1 expression or regulatory T-cell recruitment—also suggests that enzymes alone might not fully address the problem in all cases.

Beyond Enzymes: Other Approaches

Beard’s theory focuses narrowly on pancreatic enzymes, but your question about alternatives opens a broader discussion. If the goal is to make cancer recognizable to the immune system, other strategies exist outside his framework, many of which align with modern immunotherapy:

-

- Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Drugs like pembrolizumab or nivolumab block proteins (e.g., PD-1/PD-L1) that cancer cells use to tell immune cells to stand down. This doesn’t involve digesting a membrane but overrides the cancer’s “don’t touch me” signal at a molecular level.

-

- Cancer Vaccines: These train the immune system to recognize tumor-specific antigens, bypassing the need to strip away a physical barrier. They introduce cancer markers directly to immune cells, prompting an attack.

-

- Monoclonal Antibodies: Agents like rituximab target specific proteins on cancer cell surfaces, marking them for immune destruction. While they don’t digest the membrane, they enhance recognition by binding to exposed or unique tumor markers.

-

- Oncolytic Viruses: These viruses infect and lyse cancer cells, releasing intracellular contents that alert the immune system. The resulting debris acts as a natural signal, exposing cancer without relying on enzymatic breakdown.

-

- Adoptive Cell Therapies (e.g., CAR-T): Engineered T-cells are designed to recognize cancer cells regardless of their protective layers, directly targeting them based on genetic modifications rather than physical unmasking.

Connecting Back to Beard

While these modern approaches don’t stem from Beard’s theory, they share his underlying goal: overcoming immune evasion. Where Beard saw pancreatic enzymes as the body’s natural defense—akin to their role in controlling trophoblast growth—contemporary methods use synthetic or biological tools to achieve similar ends. Notably, some alternative practitioners combine enzymes with these strategies, suggesting a synergy: enzymes might weaken the tumor’s defenses, making immunotherapies more effective. For example, degrading the glycoprotein layer could expose antigens that checkpoint inhibitors or T-cells then exploit.

Final Thoughts

In Beard’s view, pancreatic enzymes are uniquely suited to digest the cancer cell’s outer membrane, a concept rooted in the trophoblastic parallel where enzymes halt placental overgrowth. This could indeed allow the immune system to finally “see” the tumor, as historical reports suggest. Beyond enzymes, though, a range of innovative therapies tackle the same problem through different mechanisms, reflecting a broader arsenal unavailable in Beard’s time. While his approach remains controversial and understudied, its core idea—that stripping away cancer’s camouflage is key—resonates with today’s cutting-edge efforts to unleash the immune system against malignancy.